Cristina Alves

Naturalist, CBEC/LIFE volunteer

On a Spring morning at CBEC, 23 third graders came for the Catch-a-Bay-Critter School Program. After hiking the Beach Trail and stopping for instructions at the pavilion, we finally headed through the salt marsh towards the water. With buckets and nets in hand, the children were ready to wade in the Bay to catch critters they came to discover!

As we reached the water, someone noticed a little head, swimming towards the beach: a snake! Not exactly a creature they were hoping to catch with their nets. For a few minutes, the little head looked towards the beach, saw people and turned in another direction, trying to find a clear path towards the marsh vegetation. Finally, the two-foot long snake found a clear track to cross the beach and disappear in the marsh. It was a northern watersnake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon). This was exciting, because it created a teaching opportunity for all to learn about this harmless, non-venomous aquatic snake.

Northern watersnakes are one of the most frequently encountered snakes on the Delmarva Peninsula and many barrier islands. They are commonly found in freshwater habitats, like rivers, streams, ponds, ditches, vernal pools, swamps and brackish water habitats, including tidal streams and the edges of salt marshes like the one we were in. These snakes are often seen swimming near the shoreline or in open water, or basking on the bank or in a tree, shrub, or log protruding over water.¹

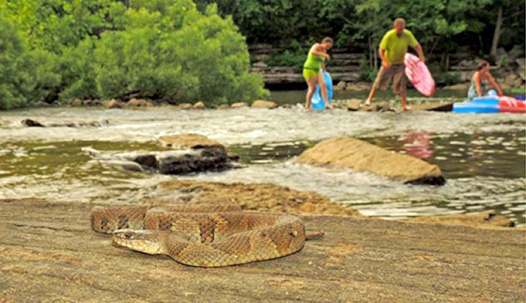

The northern watersnake is relatively large and thick-bodied, ranging between 3 and 5 feet long. They can be found in a variety of colors, but the majority will have dark blotches that often merge to look like bands of brown, black and dark green. Juveniles tend to be lighter, a sandy or reddish color on the body. As the snakes get older their color will darken and the older adult will actually have a body that is almost entirely dark brown or black, especially when dry. Their scales are keeled, which means that they have a raised ridge down the center, making them rough to the touch.2

They are excellent hunters and will feed both during the day and at night. Feeding primarily on fish, alive or dead, they will take other prey, like amphibians (frogs, toads, tadpoles and salamanders), crayfish, large insects, leeches, worms, other snakes, turtles, birds, and small mammals such as white-footed mice. They have been known to herd schools of fish or tadpoles to the edge of bodies of water where they can prey upon many at one time.3

Northern watersnakes tend to be solitary animals when active during the warmer months. Immediately before and after cold weather hibernation (called brumation for cold-blooded animals) which occurs from October to March, they become social. They congregate in communal brumation dens with other snakes during the winter in the burrows of muskrat, crayfish, meadow mice, old rock dams, or rock piles near the water.4

These watersnakes are ovoviviparous, which means that eggs incubate inside the mother’s body. They typically mate in mid-April to mid-June, with young snakes being born alive from July to September. The litter ranges in size from 4 to 99 offspring. Older, larger females tend to have larger litters.5

These snakes, especially when young, have many predators, including birds, skunks, raccoons, opossums, snapping turtles, other snakes and people. The Northern watersnake may allow a curious observer to get very close, before swimming off or slithering into the brush. When confronted or picked up, they flatten and spread their head, neck and body, looking like a venomous snake, and begin to strike and bite ferociously. Their long teeth, adapted for holding struggling fish, can inflict a nasty wound. They also release a foul-smelling musk and may defecate to discourage predators. When extremely agitated they will also regurgitate their last meal.

The northern watersnake is thick-bodied and ranges from three to five feet long. The majority have dark blotches that often merge to look like bands of brown, black and dark green. The older snakes will actually have a body that is almost entirely dark brown or black, especially when dry. PHOTO CREDIT: LISA POWERS

The Northern watersnake is the only large, thick-bodied watersnake in the Delmarva Peninsula and Chesapeake Bay area. Unfortunately, they resemble the venomous Cottonmouth or Water Moccasin (Agkistrodon piscivorus piscivorus) and Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix mokasen) and are often killed unnecessarily as a result of this mistaken identity.

Cottonmouths occur as far North as the James River in southeastern Virginia and are not found in the Delmarva Peninsula or anywhere else in Maryland or Delaware. Both Copperheads and Cottonmouth snakes are “pit-vipers”, which refers to the heat-sensitive pit located between their eyes and nostrils. This pit is not present in northern watersnakes. The venomous watersnakes also have vertical catlike pupils that may expand into circles in low light or when excited, and wedge-shaped heads with prominent venom glands, which makes the head wider than the neck. Northern watersnakes have round pupils and their head is the same width as the neck, except when agitated and displaying defensive behavior.3 Northern watersnakes do not have any heat-sensitive pits on their faces, but getting close enough to a snake to determine the presence of pits is dangerous.

As soon as the snake disappeared, that excitement dissipated. The thrill now came from the remnants of a horseshoe crab, jellyfishes, shell fragments, small Atlantic menhadens, Bay anchovies and other small fishes caught and being carefully deposited in the buckets. I knew, however, that our young Northern watersnake gave the children and adults in our group a couple of take-home messages that morning: snakes would rather not encounter humans, and it is probably as scary for them as it is for some people. If you find a snake, it is best to just leave it alone like songbirds in your garden or any other wildlife.

1 White, James F. Jr.; White, Amy W. (2007). Amphibians and Reptiles of Delmarva. Delaware Nature Society Inc., Tidewater Publishers, Centreville, MD. ISBN 978-0-87033-596-9 (paperback). Nerodia sipedon sipedon pp. 160161+ Plates 70-71).

2 Conant, R; Collins, J. (1991). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. 616 pp. Third Edition, Expanded. Peterson Field Guide, Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY. ISBN 0-395-90452-8 (paperback). Nerodia sipedon sipedon pp. 293-295 + Plate 20).

3 Tyning, T. (1990). Stokes Nature Guides: A guide to Amphibians and Reptiles. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

4 Wright, A.H., Wright, A.A., (1957). Handbook of snakes of the United States and Canada, Vol. 1, 564 pgs., Comstock Publ., Ithaca, N.Y.

5 Bauman, M., D. Metter. (1977). Reproductive cycle of the northern water snake, Nerodia sipedon (Reptilia, Serpentes, Colubridae). Journal of Herpetology, 11(1): 51-59.

Additional Resources and Information:

- Life in the Chesapeake Bay by Alice Jane Lippson and Robert L. Lippson

- Chesapeake Bay: Nature of the Estuary, A Field Guide by Christopher P. White

- Animal Diversity Web: Nerodia sipedon – University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- Northern Watersnake – Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

- Northern Watersnake – Virginia Herpetological Society

- https://www.livescience.com/52768-water-snake-facts.html – Facts About Water Snakes